It’s Tuesday night in early October 2005 and Colin McBean is lying dead on an operating table at Royal Free Hospital in Hampstead, London.

Just under an hour ago, he felt the first murmurings of a massive heart attack whilst getting in bed. After being raced to hospital and rushed through triage, over the past few minutes his body has begun to shutdown entirely.

First his speech went, then his hearing, before he was deemed immobile, meaning prior to his heart stopping he had only been able to watch as the medical team frantically tried to save his life.

“At that point I wanted to give up as the pain was too much,” McBean explains, as he peruses the rum selection at a bar in central London on a cold November morning 11 years later.

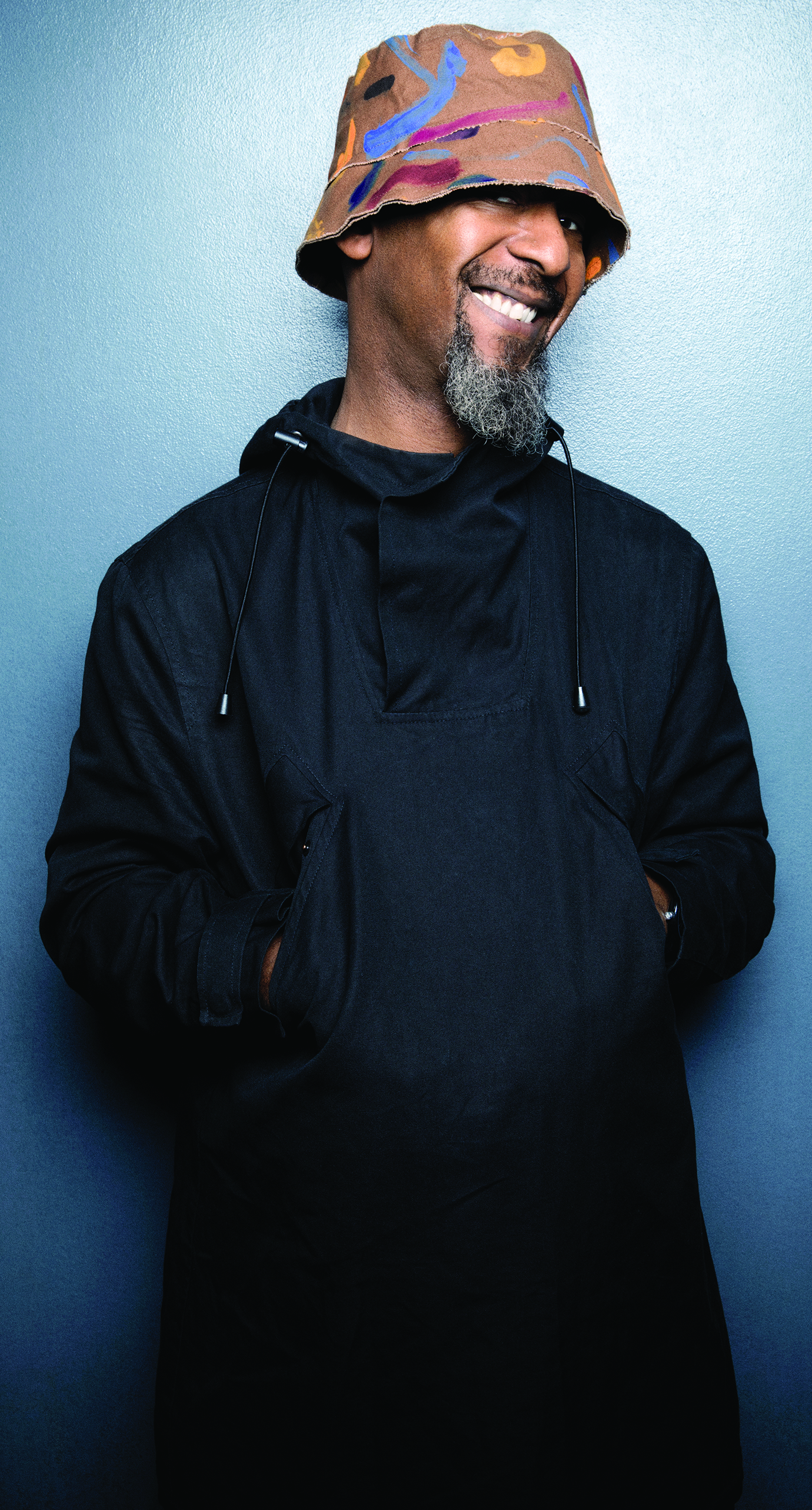

Known to the wider world as Mr. G, he settles on a Patrón, before moving to a comfortable seat in the corner of the venue. There he explains that as his heart stopped in the operating theatre, he began to feel like he was falling backwards.

“I saw the light,” he says. “All I could think is, 'You’re fucking joking. This is the end? Surely not like this'.”

After being defibrillated, the medical staff managed to revive McBean and eventually maintain a steady heart rate. Recovering in hospital, he felt blessed to be alive, but through months of heart operations he was forced to take an extended break from music.

“When I got home I was actually quite elated,” he explains, sipping his rum and ginger. “I thought I was going to have six months off to listen to records and work in the studio, but I quickly realised in that state music upsets the heart.

“I couldn’t do anything connected to emotion. I had to lie in a room in solitude and wait, so I just disappeared.

McBean’s heart attack was the first of a trio of events that put a short-term halt to his career just as he was gaining momentum, alongside taking an extended break to care for his best friend after he was diagnosed with a terminal brain tumour and his father passing away in Jamaica.

But, shortly over a decade after his heart attack, he says 2016 was the biggest year of his career. And one that’s finally seen him break to a wider audience.

See, having largely flown under the radar for the vast contribution he has made to electronic music, Mr. G has long remained one of electronic music’s last true enigmas.

RELAXED

Wearing fitted black Nike tracksuit bottoms, black Nike Mayfly trainers and a black crew-neck ALIFE jersey sweater, McBean’s personality is a world away from the dark and moody character seen on stage. Relaxed and easy-going, he says everything with a knowing glint in his searching brown eyes.

“Every time I’ve suffered a setback I’ve built it up again,” he reflects as he looks back on his career. “With each a separate beginning of where I am today.” And at 55-years-old, the road to where McBean now finds himself is much more winding than most.

Born in Derby to Jamaican parents in the early '60s, he was raised with his father as a DJ playing soul, funk and reggae.

Growing up around the music scene in the area meant that by his mid-teens he was working as a box boy for a local soundsystem, carrying equipment and setting up. After two years he graduated to become a selector.

“That’s why I have a great knowledge of sound,” he explains in his thick Derbyshire accent. “Working with the old boys served me well as an apprenticeship.”

At the same time he got a job at R.E.C.ords in the city, where his palette was opened up to everything from rockabilly to American labels like CBS Columbia Red and Philadelphia International Records.

“It taught me about music I’d never heard of,” McBean explains as he relaxes into his armchair. “So I ended up with this knowledge of music that still serves me today.”

Whilst working there, McBean began catering school at High Peak College in Buxton. It was a move that would take him away from music for the beginning of his adult life, first moving to work as a chef in Paris and Germany, before finally settling at The Dorchester in London’s Hyde Park.

“I was always collecting records, though,” he smiles. “I just never saw music as a career option at the time.”

That changed when an old friend that worked as the head designer at Zandra Rhodes, and knew McBean’s vast record collection, asked him to program music for their fashion shows at London’s Olympia.

He went on to do the same for brands including Stüssy and Betty Jackson and, already growing tired of his long shifts as a chef, he saw a world that excited him.

In his late twenties by this point, McBean enrolled at London College Of Fashion, before going on to work as a junior cutter for Stella McCartney.

But he’d got a taste for a career in music, so shortly after, having heard about a government initiative to help people move into music production, he went down to Interchange Studios in London’s Kentish Town, where he would meet Keith Franklin and Cisco Ferreira.

McBean subsequently worked with Franklin as KCC making early house music, as well as becoming a regular fixture at Notting Hill Carnival.

“Cisco and I didn’t get on at first,” he laughs. “As I didn’t know how to produce. But he soon realised my knowledge of music, and that was the beginning.”

Colin quickly realised he wanted to move in a different direction, and in 1993 formed The Advent with Ferreira, who was making techno with CJ Bolland at the time. Under the alias, the pair quickly became known for an intense and relentless sound.

MENTOR

Over the next six years The Advent became a huge force in UK techno, touring the world and sharing bills with DJs including Richie Hawtin, Kevin Saunderson and Derrick May.

“Cisco was my production mentor,” McBean explains. “I had no intention of producing my own music when we started The Advent. He was the engineer, and the master of hard funk, but sitting behind someone for all those years...” he smiles. “You learn.”

The pair would also put material out as G Flame & Mr. G on McBean’s newly-launched Phoenix G label, with his new alias named after Spiderman villain Green Goblin.

By 1999 the relentless touring became too much for him, though. “It was destroying me as a person,” McBean explains as he finishes his drink and sets it down on the table. “And there came a point where the music didn’t feel so funky anymore; 145bpm was no longer my thing.”

Shortly after, he left The Advent, and what happened next has defined his later career. Heading back to the studio, he unplugged their Akai MPC and left with it.

“I couldn’t go with nothing,” he explains. “But I didn’t realise at the time that so many people I love, like Moody[mann] and Theo [Parrish], used the MPC. I had no idea what I was doing with it though, so I spent two years in a dark room driving myself mad trying to understand it.”

Since getting to grips with the MPC, which still forms the central point of McBean’s music today, he has been steadily refining the Mr. G sound since releasing the ‘Late Nitez’ EP in 2000.

The artwork for one of his early releases read, ‘Respect the bird that jumps the nest and flies’. “I was the phoenix,” he smiles. “Rising from the flame. I’d worked alongside someone else for so long that I needed to write my music. You can hear it’s a Jeff [Mills] or Joey [Beltram] track as soon as you press play. I wanted to get to a place where people could do that with a Mr. G track.”

MUSCULAR

The muscular music McBean makes rides the gamut between house and techno, extracting parts of both and melding them into something entirely his own, whilst borrowing elements from myriad other sounds including dub reggae, funk and soul.

“I’ve always been a house-head,” he explains. “Soulful is my default setting, but I was making it with what I’d learned from The Advent. Tech-house has become a generic term for derivative music now, though,” he continues, leaning forward and shaking his head. “Which is a million miles from where I want to be. “I hate the phrase, as it’s used wrong. But it’s just a name, and I’ll always go the opposite direction to everyone else anyway.”

Something else that ties the entire Mr. G back catalogue together is the warmth in its low-end. “That’s my soundsystem days,” he smiles. “They made bass-heavy music my thing. It’s all the low-end valves in the studio, though.

“The bassline samples I use in the show are taken after the valves have been left on for a week, 24/7, so they can warm up.”

And that’s one of a few production techniques he swears by.

“I don’t work in key, tone, pitch or bpm,” he explains. “It’s about taking a sound and squashing it in until it fits, leaving the samples unclipped so the track becomes this noisy, buzzing, gnarly thing.”

McBean explains he also works at exceedingly low volume in the studio. “Today everything is about loud,” he smiles. “But if you can make a bass talk to you at no volume, it’s going to destroy the place when you turn it up. So I work quietly, then at the end I turn it up and hit play. If it doesn’t make me dance, it doesn’t get released.”

Every cut is recorded live in the studio, too. “Sometimes it’s take one,” he laughs. “Sometimes it’s take 101, which can be maddening, but it’s the only way I know. I tried dragging blocks around a computer screen but it was so sterile.”

And the live element is something that has been definitive to the renaissance in his career following his heart attack. After Rekids kick-started it again with ‘E.C.G.’ed’ in 2006, McBean hit what he calls “the digital wall”.

“My records weren’t selling and I felt lost,” he explains. “Then I heard Âme’s ‘Rej’ and it destroyed me. It was a game changer, and I didn’t think I could compete.”

He would later see Frank Wiedemann from the German production duo backstage at a live show in Japan. “He was totally honest and said he wasn’t really feeling my new stuff,” McBean smiles. “Dry as fuck. But as soon as I came off-stage he came straight back over and told me I have something really special.

“If he’d said the live show was no better I’d have probably called it a day right there, but he gave me the confidence to do something else — I also realised I’m never going to get to ‘Rej’ anyway, I’m dirty and nasty all day.”

Shortly after, McBean’s wife Cath — who he’d met whilst studying at London College Of Fashion — got a job in Market Harborough in Leicestershire in 2009. It was something that would have huge repercussions on his musical output.

“We decided to get away from London,” he smiles, looking out the window at the city he called home for so many years. “If you live your life in the mad fast-lane of nightclubs, you need the yin to the yang. I suddenly had space, and a new work rate.” What has followed is the most prolific phase of his career, with anything between eight and 10 EPs landing a year since.

DANGEROUS

The Saturday evening after DJ Mag meets McBean in London, he’s sound-checking at Le Transbordeur in Lyon, dropping basslines that shake the venue.

Wearing a pair of custom Love Denim jeans, a slate blue cashmere roll-neck sweater, grey beanie and hooded overcoat, he steps back every now and again, leans and looks towards the stacks before EQing the bottom-end to drain every last drop out of the venue’s towering D&B system.

He’s here to top the bill on the second night of three-day event We Are Reality, which sees Ricardo Villalobos and Seth Troxler go b2b on Friday, and Dixon and Âme do the same on Sunday. A few hours later he’s relaxed in the booth before going on-stage, drinking with his wife and joking with Kosme and Konstantin Sibold who are supporting him.

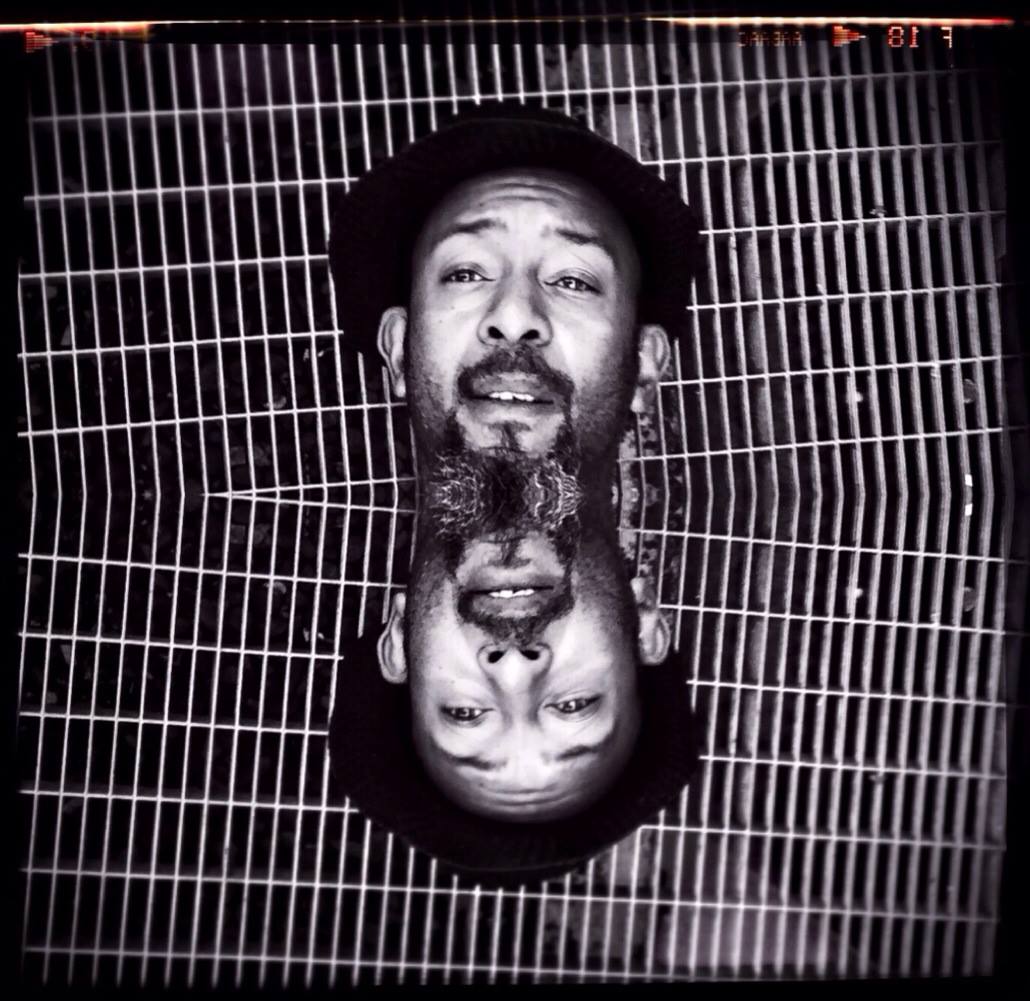

As soon as he goes on stage though, he flips into Mr. G mode. With a bucket hat pulled forward over his face, he dances with jerking movements to the familiar refrain of ‘House Is A Nation’ — the permanent introduction to his live sets.

As the song comes to a close, it’s clear he isn’t happy. Cutting the sound, he turns his back to the crowd, pulls his sweater over his head to reveal a grey Mr. G t-shirt, looks to the sound engineers at the back of the room and raises his hands as the crowd roars in approval.

Whatever impact his plea has works, as from there his set is weightier, with every bassline and kick rumbling underfoot whilst the clattering percussion punctuates the air in the packed out room. By the show’s close, his hat’s lifted off his face and he’s jumping into the crowd surrounding the stage to have his photo taken, before scissor-kicking his way back to the desk.

“I’m not showing off up there,” he explains backstage, shortly after the show. “I’m being me. If it sounds great, I wanna get down.

“Working with an MPC live, you never know what’s going to happen until you press stop. But that’s the beauty of it. Musically, I’m only in this to do things that are dangerous.”

Now, McBean has got to a stage where he is hugely selective about where he plays.

“I’m not being arrogant,” he explains. “Being on the floor at my show should be a physical experience. When I drop the bass, you should be gasping. I was finding places promise you the earth and deliver a tin-pot system.”

Something else that has been omnipresent in the later success of McBean’s career — alongside his live show — is his full-length albums.

Starting with ‘Still Here (Get On Down)’ in 2010, they have regularly documented personal tragedies or experiences. ‘State Of Flux’ marked a triumphant return in 2012 after losing his best friend the year before, with tracks like ‘Clearing Space’ fraught with the emotions of grief.

“I began to really understand what I could do with emotion on an album,” McBean explains.

“I was a mess after I lost Lex. He was my mentor and imparted so much on me, but going into the studio brought everything I was feeling out.”

Shortly after that came one of his career’s biggest game changers. In November of the same year, he was booked to play Boiler Room, which exposed him to a whole new audience.

“My life changed overnight,” he smiles as he pours a glass of Wray & Nephew. “I had no idea what it was about, I didn’t even realise it went out live, but the next morning my phone wouldn’t stop ringing. That was a definitive moment.”

RUM

Sipping on his freshly poured drink, speaking to McBean reveals his three main loves in life; music, his wife, Cath, and rum.

“Having a wife that, even through my years in the wilderness, never once told me to go out and get a job is amazing,” he smiles. “She’d always send me back in the studio and tell me I’d get there.

“I’m an insomniac, though. I sleep one night in 10 or 12. Some days I’m barely existing, and the rum is for when I get to the point I’m exhausted and need to switch off.”

Using an album as catharsis returned again in 2014, with McBean writing ‘Personal Momentz’ about the loss of his father, before ‘Night On The Town?’ dropped in 2015; a concept album about going to a club.

But it’s the recently released ‘A Good Place…?’ that marked the end of a vintage year.

“Playing Glastonbury in front of 6,000 people was one off the wish-list,” he says. “But the high point has to be 'Transient'.” As Bassculture’s 50th release, the track has since been played by everyone from D’Julz and Sasha to Matthew Dear since dropping in June, becoming one of last year’s biggest tracks on the dancefloor.

Early in the summer of 2016, Jackmaster called McBean to tell him he was at DC-10 and ‘Transient’ was being played in both rooms at the same time.

“Those are the moments,” he enthuses. “To be acknowledged like that at 55 is amazing. It’s all unexpected, as I still just love making people dance, but after I was given a second chance,” he says, reflecting on his heart attack 11 years ago, “I wanted to make it count in order to acknowledge what Lex and Cath have done for me.

“There’s no use dying, coming back and then just kicking about,” he concludes. “And that’s what I’m living for.”

Rob McCallum is DJ Mag’s deputy digital editor. Follow him on Twitter here.