We've drafted in Greg Wilson, the former electro-funk pioneer, nowadays a leading figure in the global disco/re-edits movement and respected commentator on dance music and popular culture, to bring us four random nuggets of history; highlighting a classic DJ, label, venue and record each month.

Brooklyn-born Walter Gibbons was a small and shy figure but highly assertive where music was concerned. Working at record store Melody Song Shops in the early ‘70s led to a DJ slot at gay venue Outside Inn before he secured his most celebrated residency at the after-hours Galaxy 21 in 1975.

Whilst Kool Herc juggled the breaks at his Bronx block parties, Gibbons experimented with a similar technique at Galaxy 21. With Herc, the breaks were the point at which the dancers exploded into frenzy, however what Gibbons was doing was creating a tension that built to the final payoff of a vocal or instrumental flurry – extending the break of a track like Freddie Perren’s ‘2 Pigs And A Hog’ so it ran considerably longer. Other DJs would turn up after they’d finished work themselves to hear Gibbon’s play into the early hours, gaining him the tag ‘DJ's DJ’, whilst François Kevorkian, soon after his arrival in New York from France, first found his feet accompanying Gibbons on drums.

Along with Tom Moulton, Gibbon’s is revered at the origins of remixing. He began experimenting with reel-to-reel edits and, after Ken Cayre from Salsoul Records heard him mixing between two copies of Double Exposure’s ‘Ten Percent’, he was invited to edit an extended version - his seminal ‘disco blend’ the first commercially released 12” single.

He’d work on a string of Salsoul mixes, most notably ‘Hit And Run’ by Loleatta Holloway, the first time a DJ had been let loose with the multitrack.

Gibbons left Galaxy 21 having discovered the club was secretly recording and bootlegging his sets, and that a limiter had been placed on the sound system without his knowledge. The venue closed in early ’77, soon after Gibbon’s had downed tools.

Becoming something of a journeyman on the NY club scene, unable to settle anywhere new, his uncompromising style put him at odds with both audiences and management. A fresh start across country in Seattle’s The Monastery was short-lived and he returned to New York in ‘78.

His Instant Funk ‘I Got My Mind Made Up’ remix never materialised - the suggestive lyrics clashing with his newly-acquired born-again leanings. Paradise Garage DJ, Larry Levan, would be the beneficiary, taking over the 1978 mix, which became a landmark in his career.

Gibbon’s religious beliefs/gospel playlist increasingly alienated him, but he’d enjoy a brief renaissance in 1984/85 via Strafe/Harlequin Four’s ‘Set It Off’ on his Jus Born label.

Having contracted AIDS his health deteriorated – despite failing eyesight he continued to DJ throughout, even undertaking dates in Japan. He eventually succumbed to the disease in 1994.

Tom Silverman decided he’d like to set up an independent label during his time running New York’s trade publication, Dance Music Report, which he co-founded, initially as Disco News, in 1978. He would also co-found New York’s influential New Music Seminar in 1980.

The label, Tommy Boy, was launched in 1981. He’d met Bronx DJ Afrika Bambaataa in 1980 and asked him if he wanted to make a record - the resulting track ‘Jazzy Sensation’, credited to Afrika Bambaataa & The Jazzy 5, a take on Gwen McCrae’s ‘Funky Sensation’, helped put the label on the map, but it was the next Bambaataa offering, ‘Planet Rock’, this time with the Soul Sonic Force, that sent it spiralling into space, defining the electro approach that would change the course of dance music.

Produced by Arthur Baker, ‘Planet Rock’ sparked off an electronic gold rush, which, apart from New York, would subsequently find fertile ground in Chicago and Detroit, helping birth both house and techno, whilst providing a milestone in the growth of hip-hop.

This new electro sound would be synonymous with Tommy Boy - during the coming years tracks by Bambaataa & The Soul Sonic Force, plus artists including The Jonzun Crew, Planet Patrol and G.L.O.B.E & Whiz Kid, helped set the electronic agenda. The label would also be at the cusp when it came to the raw cut and paste of hip-hop, pressing Keith LeBlanc’s brilliant collage of Malcolm X sound bites, ‘No Sell Out’, and Double Dee & Steinski’s seminal ‘Lessons’ series.

Warner Bros. took notice, buying a 50% stake in Tommy Boy in 1985, Silverman becoming a Warner vice president as part of the deal (he bought back the 50% a decade on).

1985 saw the release of another, lesser-known, catalyst track, ‘Running’ by Minneapolis-based Information Society. Inspired by ‘Planet Rock’, it can either be placed at the end of electro, one of its final classics, or at the beginning of a more electronic dance direction, which led Tommy Boy to eventually license British acts 808 State, Coldcut and LFO. The label would also have a hand in the emergence of Latin Freestyle.

In 1989 Tommy Boy would release one of the era’s great albums ‘3 Feet High And Rising’ by De La Soul, dubbed the ‘Sgt. Pepper of hip-hop’ by the Village Voice. However it was fraught with sampling issues, much of the profit syphoned off to pay licensing costs.

Tommy Boy would remain at the vanguard of hip-hop moving into the ‘90s, apart from De La Soul, its artists including Queen Latifah, Digital Underground, Naughty By Nature and House Of Pain.

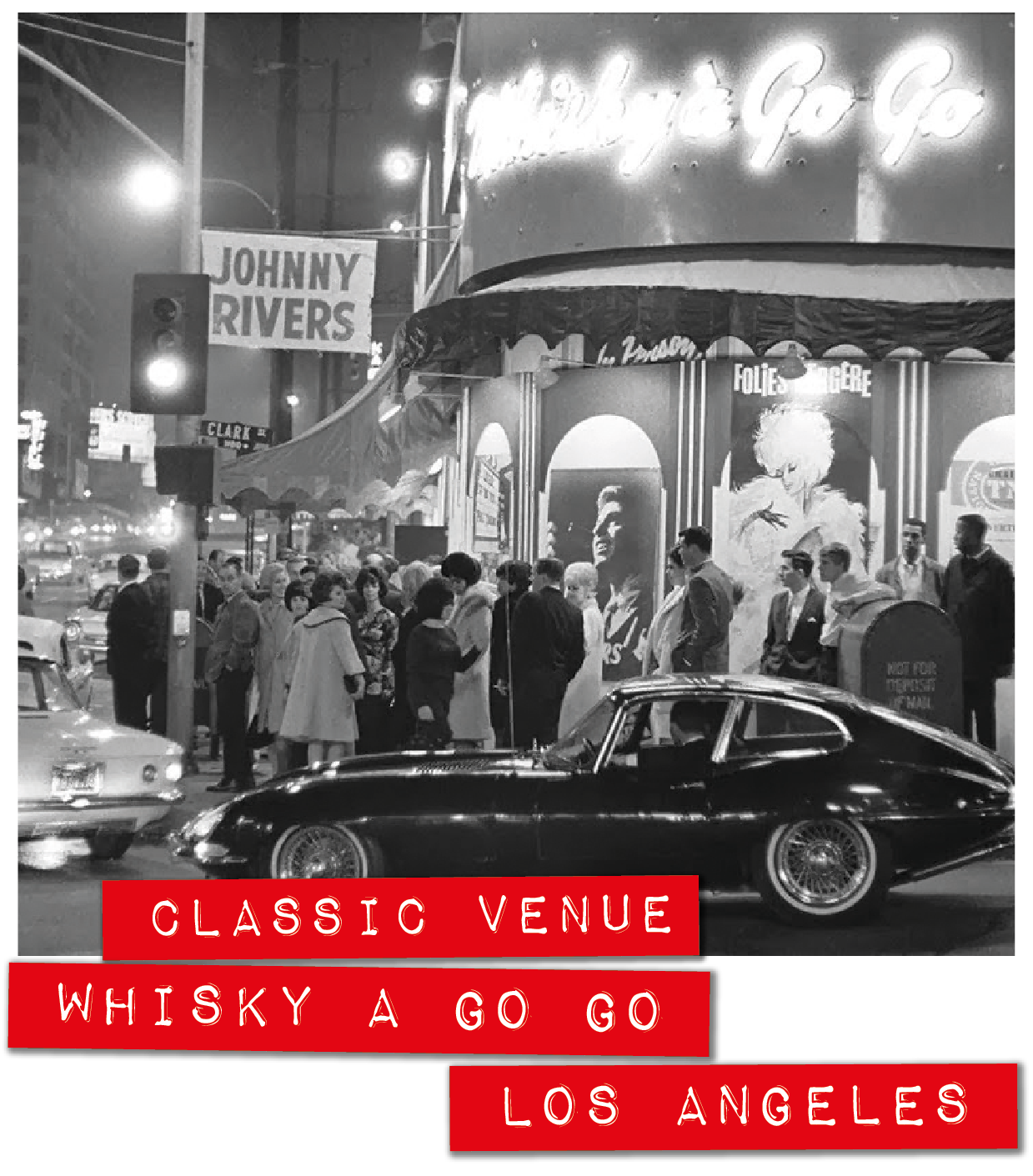

Opened in 1964 at a time when the concept of the discotheque, where recorded music was played in a nightclub setting, was still largely foreign, the Sunset Strip’s Whisky A Go Go not only acted as one of the key incubators in LA’s live band scene, but also became world-renowned for the freestyle dancing it espoused. A previous Whisky A Go Go had opened in Chicago in 1958 – this was arguably America’s first discotheque.

The French word discothèque translates as record library, and originally referred to illicit gatherings of jazz enthusiasts during the Nazi occupation of World War II, listening to vinyl 78s at clandestine spots in Paris, where jazz, due to its black roots, was outlawed by the occupying forces as degenerate. Following the war, in 1947, Paris’ Whisky à Go-Go discothèque opened, providing the inspiration behind the Chicago and Los Angeles venues of the same name.

London’s early ‘60s Mod scene was a further influence on the LA Whisky, where live music was interspaced by female DJs/dancers caged in a glass-walled booth above the audience – notably Patty Brockhurst, Rhonda Lane and Joanie Labine, who designed the official go-go-girl costume with fringed dress and white boots. Gyrating go-go dancers would soon be seen on ‘60s TV music shows like ‘Shindig’, ‘Hullabaloo’, ‘Shivaree’ and ‘Hollywood A Go-Go’.

A favoured celebrity hangout, the Whisky soon became an international phenomenon - go-go dancers beginning to pop up in clubs worldwide. The Miracles provided an anthem via their 1965 hit ‘Going To A Go-Go’, whilst US troops in Vietnam would seek their R&R at Saigon ‘go-go bars’. London’s famous WAG club was born of a Whiskey-A-Go-Go, which opened in ‘70s Soho in the very building that had housed legendary Mod venue The Flamingo.

As well as being a pioneering space for this new uninhibited approach to dancing, the club also stood alongside San Francisco’s Fillmore West as one of the most important venues for California’s band scene. It played a role in the early careers of The Byrds, Buffalo Springfield, Love, The Turtles, Frank Zappa’s Mothers Of Invention and The Doors, who were the house band for a few months until they were fired for Jim Morrison’s infamous acid-induced improvised Oedipal section in ‘The End’. Otis Redding was amongst those to record live albums in the venue (released posthumously in 1968), whilst Love paid homage to the Whisky in ‘Maybe The People Would Be The Times Or Between Clark And Hilldale’.

Given its rich ‘60s legacy, the club would fast become a hallowed LA music institution, remaining open to this day.

Chic founders, guitarist Nile Rodgers and bassist Bernard Edwards, first tasted success backing the vocal group New York City, who scored with 1973’s ‘I’m Doin’ Fine Now’.

With the addition of drummer Tony Thompson, Chic could boast one of the truly great rhythm sections. Vocalists Norma Jean Wright, Alfa Anderson and Luci Martin would also be key contributors.

They hit the ground running, going top 10 with 1977’s ‘Dance, Dance, Dance, (Yowsah, Yowsah, Yowsah)’. The follow-up, ‘Everybody Dance’, and ‘78’s ‘Le Freak’, a US #1, and ‘I Want Your Love’ continued the momentum. They also produced/wrote for lablemates Sister Sledge – 1979’s ‘We Are Family’ LP spawning a trio of classic singles that year – ‘He’s The Greatest Dancer’ and ‘Lost In Music’ in addition to the title track.

Disco pretty much held a monopoly of the #1 US chart position during ’79, numerous radio stations having switched from rock to disco, prompting a backlash by way of the ‘Disco Sucks’ movement. Its main advocate, Chicago ‘shock jock’ Steve Dahl, hit the publicity jackpot via July ‘79’s racist/homophobic record burning rally at Comiskey Park baseball stadium, at the very moment ‘Good Times’ was climbing up the US chart.

Dahl and Disco Sucks sadly achieved their objectives. Despite becoming Atlantic’s best-selling single to date, the disco-funk of ‘Good Times’, inspired by the Great Depression standard, ‘Happy Days Are Here Again’ (1929), only managed a solitary week topping the chart before being knocked off its perch by The Knack’s rock-workout ‘My Sharona’ – the tide was turning, disco fast-becoming a dirty word.

Before the early rap records were released and hip-hop as a movement became coherent, kids in the Bronx were into funk and disco. ‘Good Times’ was huge, it’s backing re-recorded just a few months on for ‘Rappers Delight’ by The Sugarhill Gang - the first rap hit, and hip-hop harbinger.

It was also central to the seminal cut-up record, ‘The Adventures Of Grandmaster Flash On The Wheels Of Steel’ (1981), while many other tracks, most notably Queen’s ‘Another One Bites The Dust’ (also included in ‘Wheels Of Steel’) took inspiration. The groundbreaking 1983 hip-hop movie ‘Wild Style’ features Grand Mixer D.ST cutting up two copies of ‘Good Times’ during its amphitheatre climax.

‘Good Times’ was Chic’s last major hit, although Rodgers & Edwards would revitalize Diana Ross’s career via a hat-trick of hits, ‘Upside Down’, ‘I’m Coming Out’ and ‘My Old Piano’. Sheila & B. Devotion’s ‘Spacer’ (1979) and Carly Simon’s ‘Why’ (1982) also benefitted from Chic’s magic, whilst Nile Rodgers would subsequently co-produce David Bowie’s biggest selling album, ‘Let’s Dance’ (1983) and ‘Madonna’s hit-laden ‘Like A Virgin’ (1984).

Written by Greg Wilson

Edited by Josh Ray

'Mr. Gibbons' illustration by Pete Fowler

Check out the previous Discotheque Archives here