Table of Contents

Image C/O Interscope Records, a division of UMG Recordings, Inc.

Gracie Abrams’ song “Us,” featuring Taylor Swift, explores the ache of lost love and the lingering questions that follow it. It blends pop with deep, raw emotion that has resonated widely with audiences. With this song, Abrams has continued to make waves, recently topping the U.K. charts and even earning a Grammy nod alongside Swift.

This track stands out on The Secret of Us (Deluxe) album, which Abrams has described as her most honest and confessional work yet. The song’s mix of vulnerability and haunting lyrics invites listeners into Abrams’ world, where she explores her inner conflict with an almost poetic sensibility. As someone with a background in English literature and creative writing, I think these lyrics open up an opportunity to examine her work in a different light — to read it almost as a modern piece of literature.

Taking this poetic approach lets us explore the lyrics through a broader literary lens, comparing the themes in “Us” to classic poetry that has examined love’s impermanence and the ache of memory. Abrams’ words echo poets like Rainer Maria Rilke, Sylvia Plath, and Elizabeth Bishop, writers who were never afraid to dive into the darker sides of love and loss.

So, in this analysis, I’ll draw on those literary voices to unpack the timeless themes in “Us.” These poets have given us insights into love as both beautiful and painful, fleeting yet unforgettable. This is just my take, of course, but I think using these literary comparisons can bring out a new perspective on Abrams’ lyrics and the way she captures the universal experience of love’s lingering effect.

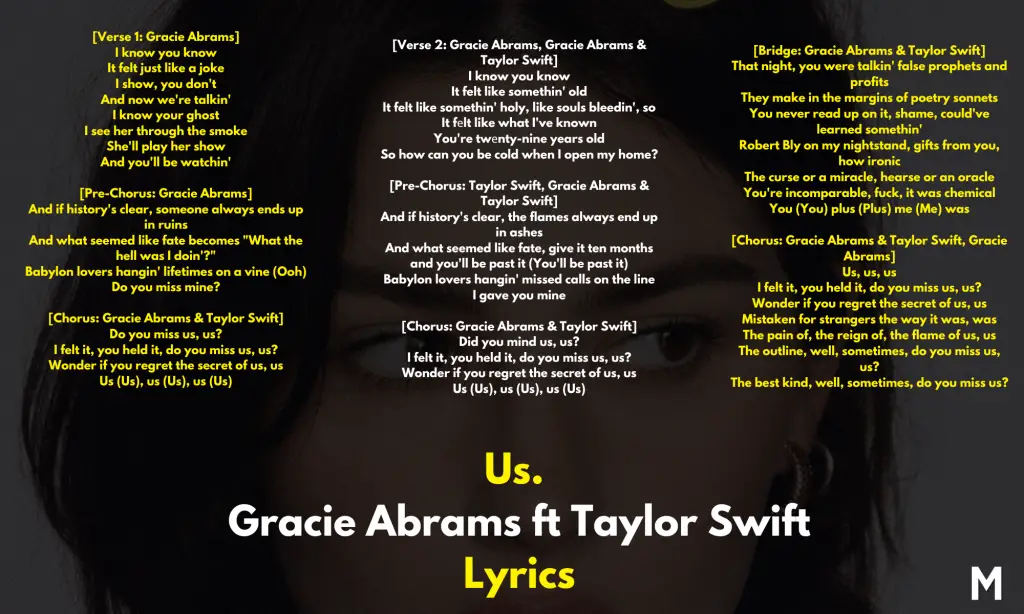

[embed]https://youtube.com/watch?v=7IcYAGAm6P8&si=CCrB7KKzyQwmqR_B[/embed]Us. Gracie Abrams Lyrics

Us. Gracie Abrams Meaning

“I know you know / It felt just like a joke”

These lines open up a conversation about how Gracie Abrams views her past relationship. By saying, “It felt just like a joke,” she’s pointing to a sense of disillusionment, as if what seemed deep and real at the time now feels shallow. This phrase suggests that maybe she gave her all, only to realize later her partner didn’t see it the same way. When she says, “I show, you don’t,” she highlights the difference in emotional investment — she was open, but her partner wasn’t.

To understand this better, we can look at Rainer Maria Rilke’s “Requiem for a Friend.” Rilke writes about losing someone close, saying that even though they’re gone, they still haunt him as a “ghost.” This connects to Abrams’ lyric about “I know your ghost,” where she also seems haunted by the memory of her ex. Just as Rilke’s memories won’t leave him, Abrams sees her ex’s “ghost” — the emotional residue of that relationship still lingers, giving her memories a haunting quality.

In both the lyrics and Rilke’s work, we see how powerful memories can be, even when relationships end. They reveal that people sometimes stay with us in ways we can’t fully let go of, like shadows or ghosts that are both painful and comforting. Abrams and Rilke both explore how love can feel everlasting, even when it’s over.

“If history’s clear, someone always ends up in ruins”

Abrams sings this line in the pre-chorus, accepting that love often leads to pain. By saying, “someone always ends up in ruins,” she’s almost predicting heartbreak. This line suggests she’s looking at love as something beautiful but fragile, something that can easily turn from joy to hurt. She’s pointing out how love has a history of being messy and painful, and she feels like this outcome was inevitable for them, too.

Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art” adds to this idea. Bishop’s poem tries to look at loss as something we can get used to, even if it’s hard. In the poem, Bishop repeats the idea that losing things is “no disaster.” However, by the end, we see she’s actually very hurt by the losses she talks about. This matches Abrams’ message about love’s “ruins,” where she’s acting tough but still feels the hurt of losing someone she loved.

In both the lyrics and Bishop’s poem, there’s an attempt to accept loss and move on, even if it’s deeply painful. Abrams and Bishop both reveal how loss, no matter how much we try to get used to it, always leaves a mark. It becomes part of us, even as we try to look forward.

“Babylon lovers hangin’ lifetimes on a vine”

With this line, Abrams uses the image of “Babylon lovers” to compare her relationship to the ancient city of Babylon, known for its beauty but also its destruction. The “lovers hangin’ lifetimes on a vine” suggests that love is like something fragile and temporary, hanging by a thread. The vine is an image of something that can easily break or wither, just like a love that didn’t last.

Sylvia Plath’s “The Couriers” offers a similar perspective. In Plath’s poem, love is portrayed as fleeting and filled with broken promises. Plath writes about “false prophets,” or people who make promises they can’t keep, which connects to Abrams’ idea of love as something delicate and easily destroyed. Both Plath and Abrams show love as a beautiful but risky thing — something that’s easy to trust in but often leads to disappointment.

Through this imagery, both Abrams and Plath reveal how love feels powerful yet vulnerable. The idea of love as something that could “hang on a vine” or be made up of “false prophets” reminds us that love, while beautiful, often has a fragile foundation that can fall apart at any moment.

“Do you miss us, us?”

This question — “Do you miss us, us?” — captures the core of Abrams’ feelings in the song. She asks if her partner still thinks about their relationship, suggesting that she’s having difficulty letting go. The repeated “us” emphasizes her longing, almost like she’s trying to relive the relationship through memory. This question also implies regret, as if she’s wondering whether she should have done something differently.

Sylvia Plath’s “Mad Girl’s Love Song” echoes this theme of longing and regret. In her poem, Plath repeatedly says, “I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead,” reflecting how, for her, memories of love are inescapable. Just as Abrams can’t stop asking, “Do you miss us?” Plath’s speaker can’t escape the haunting feeling of love lost. Both writers capture the obsessive nature of memory, how it can feel almost like a trap when you’re missing someone.

Abrams and Plath both suggest that love can stay with us long after it’s gone, making us question and relive moments over and over. This questioning shows that love, even when it’s over, can continue to have power in our lives, leaving us wondering what went wrong.

“The curse or a miracle, hearse or an oracle”

Abrams’ bridge line — “The curse or a miracle, hearse or an oracle” — compares love to something beautiful and painful. A “miracle” suggests love’s positive side, while a “curse” reveals its potential for heartbreak. The “hearse” and “oracle” add another layer, where love feels almost mystical, like it has a life and prophecy of its own, even when it’s over.

This line brings to mind Rilke’s “Requiem for a Friend,” where he reflects on how relationships can feel spiritual, yet painful. Rilke writes about the emotional weight of a lost relationship, calling it a mix of love and grief. He suggests that even though relationships may end, they continue to shape and guide us, much like an “oracle” might. Abrams’ line seems to capture that same feeling — that love is both blessing and curse, leaving us with deep questions long after it ends.

By describing love in these mystical terms, Abrams and Rilke both show that love’s impact goes beyond the relationship itself. Even after people leave, love shapes how we see the world, and its memory stays with us, sometimes as a guide and sometimes as a shadow.

“Do you mind us, us?”

The final chorus shifts the question from “Do you miss us?” to “Did you mind us?” This subtle change from asking if the partner “misses” to if they even “minded” the relationship at all suggests Abrams is moving toward acceptance. Instead of wondering if the partner feels the same longing, she’s now asking if the relationship even mattered to them. This shift hints at her own healing, as if she’s ready to accept that she might not get the answer she wants.

Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art” can help us understand this line, as her poem also tries to find peace with the pain of loss. In the poem, Bishop repeatedly tells herself that loss “isn’t hard to master,” as if trying to convince herself that she can move on. But by the end, it’s clear she’s still hurt. Abrams’ line, “Did you mind us?” echoes this acceptance mixed with pain, as if she’s letting go of her need for closure but still feeling the hurt.

Through this final line, Abrams shows how love, even when it fades, leaves a lasting impact on us. By letting go of the need for answers, she’s moving toward closure, accepting that some memories will stay with us, even if they can’t be fully understood.

Main Takeaways And Poetic Throughlines

In “Us,” Gracie Abrams and Taylor Swift delve deep into the aftermath of a love that feels like it should have lasted, leaving both haunting questions and bittersweet memories in its wake. With her recent chart-topping success in the U.K. and a Grammy nod alongside Swift, Abrams is proving that audiences are connecting with her lyrics on a profound level.

The song’s repeated refrain, “Do you miss us?” reflects a lingering sense of attachment and regret — almost like she’s caught in a loop of wondering whether her own feelings of loss are reciprocated. This exploration of heartbreak and memory ties back to the ideas we see in classic poetry, where themes of love, regret, and the painful persistence of memory are often front and center.

Abrams’ lines about “Babylon lovers” and the “ghost” of a past relationship echo sentiments found in Rainer Maria Rilke’s “Requiem for a Friend,” where Rilke talks about his memories as though they haunt him. Just as Abrams’ lyrics reflect a “ghost” she can’t let go of, Rilke describes memories of a lost friend as both a comfort and a painful weight. These shared ideas show us how both Abrams and Rilke portray love’s impact as something almost supernatural — a presence that feels real, even when it’s just a memory. Rilke’s poetry and Abrams’ lyrics suggest that, in a way, love leaves behind a ghostly imprint that lingers, whether we’re ready for it or not.

For Abrams, this haunting presence isn’t just nostalgic; it’s a reminder of a connection that, while over, still shapes who she is.

Sylvia Plath and Elizabeth Bishop explore this same sense of memory’s inescapable grip, whose poems give us a lens to see deeper into Abrams’ struggle with moving on. Plath’s “Mad Girl’s Love Song” echoes the obsessive side of memory, with her line, “I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.” That refrain reflects how memories can pull us back to the past, much like Abrams’ repeated “Do you miss us?” — a question that almost seems directed at herself as much as her ex. Bishop’s “One Art” tackles loss as something unavoidable, something we have to face no matter the pain.

Bishop’s mantra that “the art of losing isn’t hard to master” is echoed in Abrams’ song, which acknowledges the inevitability of love’s end but still holds onto the hurt. Together, these poets and Abrams herself show that love’s imprint on us isn’t just emotional; it’s almost like a part of us that we carry forward, whether or not we find answers to the questions left behind.

The post Us. Gracie Abrams Lyrics And Meaning: Dissecting Love, Loss, and Poetic Regret appeared first on Magnetic Magazine.