Table of Contents

Image C/O

Billie Eilish & Interscope

Billie Eilish has always dug deep into themes like emotional turmoil, vulnerability, and self-reflection. In her song “Blue,” she continues to explore these ideas, but with a focus on regret, sadness, and the heavy influence of family dynamics. “Blue” is about more about the inherited trauma that shapes who we are and how we deal with relationships than anything else (at least in my opinion).

In this article, I’m using my background in English lit and creative writing to take a closer, more poetic look at the lyrics. These are just my personal thoughts, but I’ll be drawing connections between “Blue” and the works of poets like Emily Dickinson, W.H. Auden, and Sylvia Plath—writers who’ve explored similar motifs and landscapes. Through this lens, I hope to shed light on the song’s deeper layers and how Billie Eilish taps into timeless themes of grief, loss, and unresolved feelings. Let’s dive into how “Blue” hits with similarly to other literary explorations of emotional struggle.

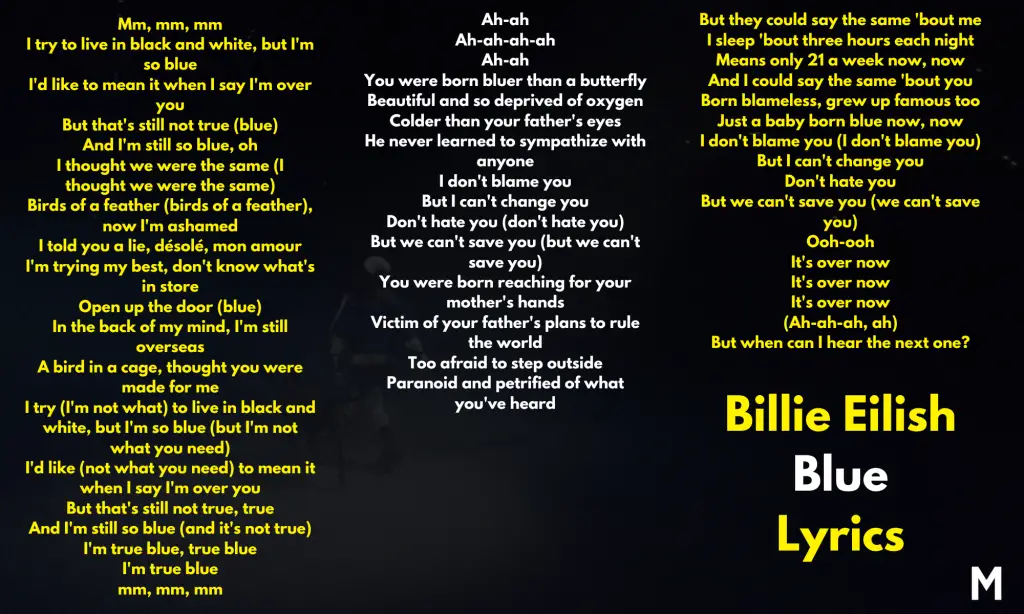

[embed]https://youtube.com/watch?v=mZqiawnNCQg&si=cFBbDYI4GQnCu4FZ[/embed]Billie Eilish’s Blue Lyrics

Billie Eilish Blue Meaning

These song lyrics hit hard, diving deep into unresolved feelings, regret, and the emotional baggage we carry from our past—especially family trauma. As I read through them, I couldn’t help but think about how poets like Emily Dickinson, W.H. Auden, and Sylvia Plath have been wrestling with these same ideas for years.

In I measure every Grief I meet, Dickinson talks about how grief is impossible to neatly box up or measure—just like in this song, where the speaker tries to live “in black and white” but can’t escape feeling “blue.” Then there’s Auden’s Funeral Blues, where the crushing weight of loss and disappointment mirrors the speaker’s regret over a relationship they thought was perfect but now feels ashamed of. And of course, Plath’s Daddy digs into the inherited trauma that shapes us—just like how the song looks at the way family dynamics play into emotional scars.

These themes—emotional complexity, lingering sadness, and family baggage—run through the lyrics, and by connecting them with these poets, we get a better sense of how universal these struggles are. Let’s dig into how these lines capture that feeling of being stuck between wanting to move on and still feeling trapped in the past.

“I try to live in black and white, but I’m so blue…”

The song opens with the striking line, “I try to live in black and white, but I’m so blue,” immediately setting the stage for the emotional complexity at play. The speaker is trying to reduce their emotions to something simple, clear-cut, and manageable—”black and white”—but instead, they are overwhelmed by a deep and persistent sadness, symbolized by the color “blue.” This tension between wanting clarity and feeling overwhelmed by emotions is a struggle that many experience, and it resonates deeply with the way poets like Emily Dickinson have written about grief and sadness.

In I measure every Grief I meet, Dickinson reflects on the unquantifiable nature of grief, saying, “I wonder if It weighs like Mine— / Or has an Easier size.” Here, she explores the idea that pain and grief cannot be easily measured or understood, much like the speaker in the song, who is trying but failing to categorize or simplify their sadness. The desire to live “in black and white” is an attempt to impose order on emotions, but as Dickinson shows, grief defies easy categorization. In the same way, the speaker in the song admits they can’t escape the emotional turmoil of feeling “blue,” despite their best efforts.

The second line, “I’d like to mean it when I say I’m over you,” adds to this sense of unresolved emotion. It’s a candid admission that, despite wanting to be past the relationship, the feelings linger. In W.H. Auden’s Funeral Blues, the speaker expresses a similar longing for emotional closure in the face of overwhelming loss: “He was my North, my South, my East and West.” Just as the speaker in the song wishes they could move on, Auden’s speaker is unable to let go of the significance the lost relationship once held in their life. Both speakers are trapped in a state of emotional conflict, wanting to declare an ending but finding that the feelings are still too present, too powerful.

“I thought we were the same / Birds of a feather, now I’m ashamed…”

The line “I thought we were the same” expresses a powerful realization: the speaker once felt a deep connection with the other person, believing them to be “birds of a feather,” but now feels ashamed of that belief. This moment of self-awareness reflects the common experience of idealizing a relationship, only to later see the flaws or mistakes that were overlooked in the past. The idea that the speaker has come to view the relationship with a sense of regret or shame is key to understanding the emotional complexity of the song.

This sentiment connects strongly to Auden’s Funeral Blues, where the speaker laments, “Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone.” In both the song and Auden’s poem, there’s a sense of finality and disillusionment. The speaker in the song feels ashamed because they misjudged the depth or meaning of the connection, much like Auden’s speaker, who demands the world stop as they come to terms with the overwhelming grief of loss. There is a shared realization that what was once seen as central and defining now only brings pain and regret.

Additionally, the shame the speaker feels in the song could stem from the lies and mistakes they admit to: “I told you a lie, désolé, mon amour.” This moment of confession adds weight to the regret, suggesting that the speaker not only misunderstood the relationship but actively contributed to its downfall. The complexity of admitting personal fault, while still being trapped in lingering sadness, mirrors Sylvia Plath’s reflections in Daddy. Plath writes, “I made a model of you,” expressing how she built an image of her father that she later realized was flawed. Both the song’s speaker and Plath’s speaker are coming to terms with the emotional baggage they carry from relationships that were idealized but ultimately damaging.

“In the back of my mind, I’m still overseas / A bird in a cage, thought you were made for me…”

This section deepens the song’s exploration of emotional entrapment. The speaker is stuck—”overseas” in their mind, perhaps metaphorically representing emotional distance or unresolved feelings. The image of a “bird in a cage” adds a layer of being trapped by expectations, either their own or those placed on them by others. The belief that the other person was “made for me” shows that the speaker once saw the relationship as perfect or destined, but now they feel confined by that belief.

This imagery of a bird in a cage speaks to the idea of emotional constraint, much like the experiences described in Sylvia Plath’s Daddy. Plath writes, “I have always been scared of you,” revealing how her relationship with her father left her feeling trapped and fearful, bound by expectations and unresolved trauma. In the same way, the speaker in the song is grappling with the realization that the person they thought was “made for me” was, in fact, not the key to their emotional freedom but rather a source of confinement.

The sense of being “overseas” also evokes a feeling of disconnection, as if the speaker is stuck in a distant place, both physically and emotionally. In Dickinson’s I measure every Grief I meet, the speaker reflects on the isolating nature of grief: “And though I may not guess the kind— / Correctly—yet to me.” Just as Dickinson’s speaker feels disconnected from fully understanding others’ grief, the speaker in the song is emotionally separated from their past relationship, still carrying unresolved feelings that keep them at a distance.

“I don’t blame you / But I can’t change you / Don’t hate you / But we can’t save you…”

These lines introduce a sense of resignation. The speaker recognizes that while they don’t blame the other person for their emotional state, they are powerless to change or “save” them. This recognition is a major turning point in the song. The speaker is coming to terms with the limits of their ability to influence the other person’s emotions or behavior, as well as the emotional damage caused by the relationship. This is a common theme in poetry, particularly in works that explore inherited trauma or emotional scars.

In Plath’s Daddy, she writes, “You do not do, you do not do / Any more, black shoe.” These lines show Plath’s speaker also reaching a point of resignation, acknowledging that the relationship with her father has been permanently damaged and cannot be saved or repaired. Both Plath’s speaker and the speaker in the song have come to understand that some emotional wounds are beyond their ability to heal, either in themselves or in others.

In Auden’s Funeral Blues, the speaker similarly faces the harsh reality of loss: “The stars are not wanted now; put out every one.” There is a finality in these lines, as Auden’s speaker realizes that no amount of emotional effort can bring back what has been lost. In the song, the speaker’s admission that “we can’t save you” mirrors this emotional resignation, accepting that the relationship has reached a point where no further effort will change the outcome.

Conclusion

In my opinion, these lyrics effectively explore the emotional complexities of regret, unresolved sadness, and inherited trauma. By reflecting on personal accountability and the limits of emotional control, the speaker navigates the difficult terrain of coming to terms with past relationships and the emotional scars that linger. Through comparisons with the works of Emily Dickinson, W.H. Auden, and Sylvia Plath, we can see how the song’s themes echo long-standing literary explorations of grief, trauma, and emotional entrapment.

The repeated refrain of “It’s over now” doesn’t necessarily provide a sense of closure, but it reinforces the idea that the speaker is moving toward acceptance, even if the emotional weight remains. Much like the poetry of Dickinson, Auden, and Plath, the song doesn’t offer easy answers, but it presents a raw and honest reflection on the human experience of sadness, loss, and self-awareness. The strength of these lyrics lies in their vulnerability and the willingness to confront the messy, unresolved aspects of human relationships.

The post Billie Eilish Blue Lyrics And Meaning: Poetic Reflections on Grief and Family appeared first on Magnetic Magazine.