Table of Contents

Images Credit To Daughters Of Cain Records

Ethel Cain’s Amber Waves, the closing track from her project Perverts, is haunting in its exploration of addiction, loss, and numbness. It’s a song that feels both intensely personal and eerily universal, weaving together imagery that lingers long after the music fades.

Using my background in English literature and creative writing, I’ll unpack these lyrics more poetically, offering my own interpretations. These are just my thoughts, but by layering in references to classic poetry and literature, I hope to provide a fresh lens for understanding the song.

Cain’s ability to craft immersive, emotionally complex narratives in her music feels similar to the depth you’d find in literary works by authors like William Faulkner or poets like T.S. Eliot and Philip Larkin. Amber Waves feels like the culmination of the themes on Perverts—a project steeped in drone, slowcore, and ambient textures. This song doesn’t just evoke feelings; it paints a cinematic image of emotional detachment and longing.

Here, we’ll dig into the lyrics and see how timeless themes of addiction and escape resonate, stretching across literature, Southern Gothic imagery, and Cain’s unique musical storytelling.

[embed]https://youtube.com/watch?v=UcuQyY1iG3A&si=VXrXy5Z16FNhyMUe[/embed]Amber Waves at a Glance

- Addiction and Escape: The recurring “amber waves” imagery suggests something both beautiful and suffocating—perhaps substance use or a longing for fleeting relief.

- Emotional Numbness: Lines like “I can’t feel anything” highlight the speaker’s complete detachment, reflecting themes of existential malaise and denial.

- Heartbreak and Loss: The song explores a relationship unraveling, but the speaker masks their pain with resignation and bitterness, leaving their true emotions buried.

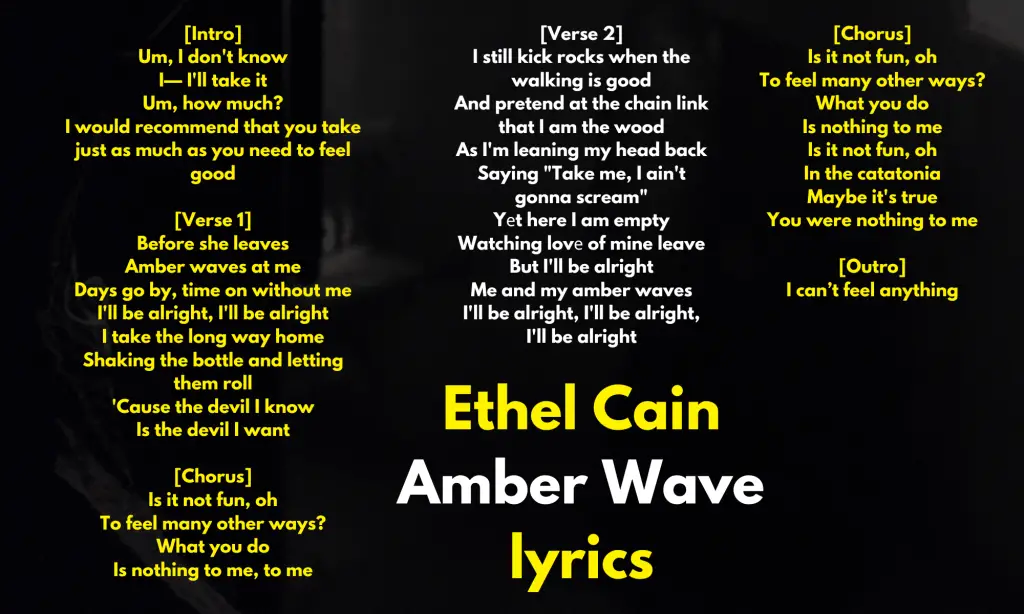

Amber Waves Lyrics

Ethel Cain Amber Waves Meaning

“Um, I don’t know / I— I’ll take it / Um, how much?”

The song opens with a conversation that feels hesitant and unsure. The speaker is deciding how much of something—probably a substance or escape—they need to feel okay. The line “just as much as you need to feel good” sounds like advice, but it’s also a warning. This sets the stage for the rest of the song, where the speaker wrestles with how much they need to numb their emotions.

This opening reminds me of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. In that poem, Eliot uses fragmented dialogue to show people who feel disconnected from themselves and their world. One line says, “I can connect / Nothing with nothing,” which captures the same kind of uncertainty we see here. Both works suggest a search for something to hold onto, even if it’s unclear what that might be.

The tone here is quiet and unsure, but it hints at the deeper struggles the speaker is about to reveal. This uncertainty, paired with a desire to feel “good,” makes us wonder if the speaker knows how far they’ve already fallen into a cycle of addiction or detachment.

“Before she leaves / Amber waves at me”

This line introduces the image of amber waves, which appear throughout the song. Amber is golden and beautiful, but it’s also heavy—it traps things in place. In this context, I believe “amber waves” represent addiction or a temporary escape. They might feel comforting, but they also keep the speaker stuck in a cycle they can’t break free from.

In William Wordsworth’s Lines Written a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey, he writes about nature’s beauty, saying it offers “tranquil restoration.” For Wordsworth, moments like amber waves would be healing, but in this song, they seem more like a burden. The amber here isn’t restorative—it’s a weight that keeps the speaker tied to their pain.

The use of “before she leaves” makes this moment feel even heavier. Whether “she” is a person or a metaphor for hope, the speaker is watching her slip away, and all they’re left with is the comfort of amber waves—a comfort that’s ultimately hollow.

“I take the long way home / Shaking the bottle and letting them roll”

This line paints a clear picture of avoidance and risk. Taking “the long way home” suggests the speaker is delaying facing their reality, while “shaking the bottle” might refer to gambling with their emotions or relying on substances to get by. The randomness of “letting them roll” implies a lack of control, as if the speaker is leaving their fate up to chance.

T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land has a similar sense of despair and randomness. One line says, “I will show you fear in a handful of dust,” which suggests how something small and insignificant can carry enormous weight. In this song, the bottle might seem like a small thing, but it holds the speaker’s struggles with addiction and self-destruction.

The phrase “the devil I know / Is the devil I want” adds to this sense of resignation. The speaker is choosing the pain they’re familiar with because the unknown feels scarier. This reminds me of Philip Larkin’s Aubade, where he writes, “Courage is no good: / It means not scaring others.” Both the poem and the song show people who feel stuck in their suffering, unable to imagine a way out.

“Is it not fun, oh / To feel many other ways?”

The chorus introduces a sarcastic tone, as if the speaker is mocking the idea of joy or emotional variety. The rhetorical question “Is it not fun?” feels bitter, like the speaker has been told they should try to feel differently but can’t bring themselves to do it. The repetition of “nothing to me” reinforces their emotional detachment, suggesting they’ve shut themselves off from feeling anything at all.

This detachment reminds me of Philip Larkin’s Aubade, where he describes life as a monotonous routine: “Postmen like doctors go from house to house.” Just like in the song, Larkin’s speaker seems numb to the world around them, going through the motions without finding meaning.

In the context of the song, the chorus feels like the speaker’s attempt to distance themselves from their pain. By mocking their own emotions and repeating “nothing to me,” they’re trying to convince themselves they don’t care—but the bitterness in their tone suggests otherwise.

“Yet here I am empty / Watching love of mine leave”

This line is one of the most vulnerable in the song. The speaker acknowledges their emptiness and the loss of someone they care about, but they don’t express deep grief. Instead, the word “empty” captures their emotional numbness, showing how detached they’ve become from their own pain.

T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land has a similar moment of loss and emptiness. One line says, “These fragments I have shored against my ruins,” which reflects a desperate attempt to hold onto something in the face of emotional collapse. In both the song and the poem, the speakers are watching something important slip away, but they can’t find the energy to hold onto it.

The repetition of “I’ll be alright” earlier in the song feels especially hollow now. It’s clear the speaker is trying to reassure themselves, but moments like this show how deeply they’re struggling. They might say they’ll be fine, but their emptiness tells a different story.

“I can’t feel anything”

The song ends with this stark and devastating line. After all the self-reassurance and attempts to numb their pain, the speaker admits the truth: they’re completely disconnected from their emotions. It’s a quiet ending, but it carries the weight of everything that came before it.

Philip Larkin’s Aubade ends in a similarly bleak way, with the line, “Unresting death, a whole day nearer now.” Both the poem and the song confront the finality of their situations, offering no easy answers or resolutions. Instead, they leave us with the sense that the struggle will continue, even if the speaker can’t feel it anymore.

This ending is powerful because it doesn’t try to fix anything. Instead, it forces us to sit with the speaker’s numbness and wonder what brought them to this point. It’s a haunting conclusion that lingers long after the song is over.

Connecting All The Dots

The lyrics of Amber Waves grapple with addiction, emotional numbness, and the bittersweet longing for something just out of reach. The recurring image of “amber waves” is central to understanding the song’s core themes. On one level, it recalls the pastoral warmth of “amber waves of grain” from America the Beautiful, but here, those waves seem to suffocate rather than inspire. It’s a symbol of escape—beautiful and intoxicating, yet it traps the speaker in a cycle of self-destruction.

This duality mirrors the broader themes in Perverts, a project where Cain uses experimental soundscapes and intimate lyrics to explore shame, longing, and the weight of emotional isolation.

The line “I can’t feel anything” at the song’s conclusion connects deeply to the existential dread explored in Philip Larkin’s Aubade. In that poem, Larkin reflects on the inevitability of death and the numbness it brings, writing, “Postmen like doctors go from house to house.” This image of life as a monotonous routine echoes the resignation in Cain’s lyrics. In Amber Waves, the speaker’s numbness feels like both a defense mechanism and a prison.

Like Larkin, Cain isn’t offering solutions—she’s simply mapping the emotional landscape of someone who’s stuck, searching for meaning but finding only emptiness.

What makes Amber Waves even more haunting is how it mirrors the fragmented voices and desolation of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. In particular, Eliot’s line, “I can connect / Nothing with nothing,” resonates with the speaker’s emotional detachment. Just as Eliot’s poem is about the collapse of connection in the modern world, Cain’s lyrics explore what it feels like to watch love slip away while remaining paralyzed by one’s own pain.

Together, the song and these poems underscore a timeless truth: the human struggle to reconcile longing with loss, and to find solace in a world that often feels indifferent. Cain’s ability to blend deeply personal storytelling with universal themes puts Amber Waves in conversation with these literary works, revealing the power of art to bridge emotional isolation.

The post Ethel Cain Amber Waves Meaning And Lyrics: Emotional Void and Escape appeared first on Magnetic Magazine.